With the coronavirus pandemic worsening drastically this summer, executives at Suffolk Construction, an AGC of New York State LLC and Rhode Island Chapter-AGC member figure it’s only a matter of time before a worker shows up sick to one of its many job sites across the country. But for COVID-19 to spread at one of those sites, it will have to jump through more hoops than a circus tiger.

Preventing transmission of COVID-19 is a test the nation has failed, but through mid-July, Boston-based Suffolk was a notable success story, with its multipronged approach to workplace safety having resulted in zero documented cases at job sites.

Each day before they arrive, workers fill out an online form that screens for potential risks by asking them if they have traveled to a hot spot, if they believe they have been exposed to an infected person and if they have had any symptoms of illness. Jobsites also have “COVID ambassadors,” according to Alex Hall, Suffolk’s executive vice president for business solutions. Their job is to monitor employees and ensure they are wearing personal protective equipment and adhering to social distancing guidelines.

To augment those efforts, Suffolk was among the early adopters of two technological solutions that are proving effective in the field.

The first is the Proximity Trace solution from Norwalk, Connecticut-based Triax Technologies, an AGC of Colorado Building Chapter and TEXO member, featuring wearable devices that vaguely resemble the beepers and pagers of the 1990s. The devices alert workers when they are too close to each other and collect data on all close-contact interactions to simplify contact tracing.

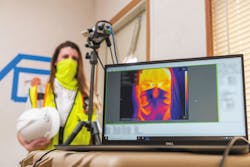

The second is a forward-looking infrared camera installed at each job site to take workers’ temperatures and quickly identify anyone running a fever. Sensors installed in FLIR cameras detect infrared radiation emitting from a heat source such as humans. The technology is used in a variety of applications, including piloting aircraft in low-visibility conditions, search-and-rescue operations and border security, and due to the pandemic, you can add the construction industry to that list.

Hall says Suffolk began looking for ways to shield its workers from COVID-19 in mid-February, before the virus had gained a strong foothold in the United States, and began implementing its solutions in early April.

“We’ve been at this for a while now,” Hall said in mid-July. “Our thinking more than anything was about how we keep people safe on our job sites, and it became clear to us very quickly that there was never going to be a silver bullet for this. It required different technologies to make sure that we were doing the right thing. It’s been a multilayered approach, and we keep on learning.”

WEARABLE DEVICES

Proximity Trace involves four components: TraceTag devices worn by workers’ on their hard hats or clothing, small gateway devices positioned in high-traffic areas, the cloud and the platform’s dashboard display.

TraceTags sound an audible alert and flash their red LED lights when workers get within close proximity of each other. As the separation distance decreases, the devices can intensify their alert to signal increasing risk, and they don’t stop until the workers reestablish adequate spacing. The alarm can be silenced or temporarily disabled with the push of a button, allowing workers with appropriate PPE to work in tight quarters without generating an alert.

TraceTags continuously collect data on close-contact interactions, noting which workers are near each other and for how long. Gateways installed at entrances and exits harvest data from TraceTags automatically as workers pass by them and upload it to the cloud. Supervisors can log into a secure website to view the data on the platform’s dashboard display using a smartphone, computer or other Internet-connected devices.

Should an employee test positive for COVID-19, the supervisor can print out a contact-tracing report immediately, allowing the company to identify and isolate anyone who may have had contact with the sick worker. Lori Peters, vice president of marketing for Triax Technologies, said the detailed reports make quick work of an otherwise laborious task.

“The process of contact tracing previously would have taken them hours or days to do manually, and it would rely on schedules and memories, which can be unreliable,” Peters says. “This is a very accurate way to identify those who may have been affected. Rather than potentially having to close down an entire site, they have it isolated among a few individuals.”

Using a cellular connection, gateways automatically deliver software updates to TraceTags. The wearable devices are assigned to workers for the duration of a job, have a rechargeable battery and can go several months on a single charge. Workers typically take them home with them, but since TraceTags don’t track workers’ location or movement offsite, privacy concerns are eliminated.

Peters says TraceTags are purchased, not rented, and more than 15,000 were in the field as of mid-July. For a crew of 100 workers, they cost about a dollar a day for the first six months — about $18,000 — and afterward, there is a monthly subscription fee of $2 per device. That fee is waived if customers enroll in Triax’s flagship Spot-r platform, which collects data to offer real-time insights into workers’ productivity and safety.

Suffolk has begun using TraceTags on almost all of its job sites and has gotten positive feedback from workers, Hall says. “Especially on those job sites that had early scares or potential exposures early on,” he says. “They were the ones saying that this is above and beyond what they were expecting us to do, and it’s something they really appreciate.”

Other construction companies are following suit. In July, Skanska USA, a member of multiple AGC chapters, announced that it had outfitted 150 workers with TraceTags while building an addition to the CHA Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center in Los Angeles.

FLIR CAMERAS

Early in the pandemic, Suffolk had an employee with a handheld thermometer screening employees at the entrance to every job site. But now, FLIR cameras are installed at entranceways, and a supervisor views the thermal images on a remote monitor. FLIR cameras measure workers’ skin temperature rather than their core temperature, and supervisors are looking for outliers — those with temperatures at least 1.8 to 2.5 degrees higher than their peers.

FLIR cameras greatly reduce the time it takes to screen all workers entering a large job site, Hall says, so workers don’t have to wait in long lines, potentially exposing themselves to the virus. The risk of transmission also is reduced because the employee with the handheld thermometer is removed from the equation. The results are well worth the higher cost of FLIR cameras, Hall says.

“These devices are more expensive than the handheld devices, but the real benefit is how quickly we can bring people onto job sites,” Hall says. “We need to do that quickly enough that they can maintain social distancing. Also, the second they’re standing in line to be tested, they’re on the clock, so this technology helps in terms of safety and cost-efficiency.”

Hall says Suffolk will continue to use TraceTags and FLIR cameras until a vaccine is widely available or the rate of transmission is greatly reduced. The company also is exploring another layer of screening in which a regular camera would be installed next to a FLIR camera so artificial intelligence programs could look for employees who are sneezing, coughing, sweating or displaying other symptoms.

“I don’t think you’re going to see that in the next few months, but it’s a technology that we’ve got our eye on,” he said. “It’s just another layer of protection that we can introduce to keep people on job sites safe.”

Hall says Suffolk’s multilayered approach to worker safety has yielded some surprising behavioral results. It turns out that when workers fill out safety forms daily, see COVID ambassadors roving on-site and see FLIR cameras and TraceTags in use, safety stays top of mind. “I think there’s definitely been a behavior modification on a lot of our job sites,” he says. “Our safety statistics for the months of April and May were much improved, and I think it’s just a really interesting phenomenon. The more awareness we can create about people’s own physical well-being, the better it is for controlling risk on the job site.”